Hurricane Katrina, Race and Class: Part I

I have been in Pensacola, Florida since late-Tuesday because my house in Mobile still is without electricity. I'm doing okay here, but I look forward to getting back home as soon as electricity is restored. The University is supposed to reopen on September 6th, but that may change, depending on conditions. Yesterday and today the gas stations here in Pensacola were mainly without gas, and I waited in a long line at the one station that (only briefly) had gas to offer. It's scary to see people begin to panic when basic commodities are in short supply; I can only imagine to what degree such a sense of panic must be magnified nearer to the epicenter, where essential necessities such as water, food, and sanitation are in severe shortage.

From my vantage — geographically and emotionally near the disaster, but safely buffered from its worst deprivations — much of the press coverage has not adequately dealt with the most difficult social issues that mark this still unfolding catastrophe. It is difficult to avoid concluding that one important cause of the slow response to the debacle has to do with the fact that most of the people who are caught up in it are poor and black. Here in Pensacola I keep hearing blame expressed towards the victims: "they should have heeded the call to evacuate." Even the FEMA chief said as much in a news conference today. So where, I must ask, were the busses he should have provided to take them away before Katrina hit? Where were the troops to supervise evacuation? Where were the emergency shelters and health services? People who ought to know better do not seem to understand or acknowledge the enormous differential in available resources — access to transportation, money, information, social services, etc. — that forms the background to this human catastrophe. Terms such as "looting" are tossed about in the press and on TV with no class or race analysis at all. In recent news reports, there is an emerging discussion of the political background to the calamity: the Bush administration's curtailment of federal funding for levee repair in order to pay for the war in Iraq, rampant commercial housing development on environmentally protective wetlands, financial evisceration of FEMA, and so on. But there's been little or no discussion of the economic background that makes New Orleans a kind of "Third World" nation unto itself, with fearsomely deteriorated housing projects, extraordinarily high crime and murder rates, and one of the worst public education systems in the country.

Major newspaper editors and TV producers have prepared very few reports about issues of race in this disaster, and those reports that have appeared so far seem to me deeply insufficient in their analysis of endemic class and race problems. I've been communicating with a national magazine reporter friend of mine since Tuesday night about the issues of race and class in this catastrophe; here's my email comment on this topic from earlier today:

Michael Moore also had this to say in a letter to President Bush circulated today:

(See Michael Moore's full letter here.)

A member of the Congressional Black Caucus had to remind reporters today to stop referring to those displaced by the flooding with the blanket term "refugees" (recalling, of course, the waves of Haitian or Central American or Southeast Asian refugees who sought shelter in the US): these people are citizens, she said, deserving of the full protections guaranteed to all Americans.

The federal government promised on Wednesday that those receiving food stamps could get their full allotment at the beginning of September, rather than the usual piecemeal distribution throughout the month. How very generous. What these people need is relief money and access to services now — even the 50,000 or so exhausted and traumatized people whose images we've seen at the N.O. Superdome and at the Civic Center are just a few of the far larger number of those residents of the region displaced by the hurricane, many of whom live from monthly paycheck to paycheck. It will be months at the very least before these people can return home; their jobs may be gone for good. The mayor of New Orleans was actually caught off camera crying in frustration today at the slow pace of the federal response.

If there is a hopeful side to this tragedy, it is perhaps that Hurricane Katrina's damage and efforts to relieve those displaced by the storm may spark a wider national discussion about the ongoing and unaddressed issues of race and economic disparity in America. If that doesn't happen, I fear that there will be even further deterioration in the living conditions and economic predicament of those left destitute and homeless by Katrina — a situation in which our own government's years of neglect must be included as a crucial contributing factor. We must not let such a deterioration of conditions for those hardest hit by Katrina occur.

What happens next, when tens or hundreds of thousands of Americans require long-term recovery help, will be an important barometer of our society's ability to heal itself.

—Lincoln

From my vantage — geographically and emotionally near the disaster, but safely buffered from its worst deprivations — much of the press coverage has not adequately dealt with the most difficult social issues that mark this still unfolding catastrophe. It is difficult to avoid concluding that one important cause of the slow response to the debacle has to do with the fact that most of the people who are caught up in it are poor and black. Here in Pensacola I keep hearing blame expressed towards the victims: "they should have heeded the call to evacuate." Even the FEMA chief said as much in a news conference today. So where, I must ask, were the busses he should have provided to take them away before Katrina hit? Where were the troops to supervise evacuation? Where were the emergency shelters and health services? People who ought to know better do not seem to understand or acknowledge the enormous differential in available resources — access to transportation, money, information, social services, etc. — that forms the background to this human catastrophe. Terms such as "looting" are tossed about in the press and on TV with no class or race analysis at all. In recent news reports, there is an emerging discussion of the political background to the calamity: the Bush administration's curtailment of federal funding for levee repair in order to pay for the war in Iraq, rampant commercial housing development on environmentally protective wetlands, financial evisceration of FEMA, and so on. But there's been little or no discussion of the economic background that makes New Orleans a kind of "Third World" nation unto itself, with fearsomely deteriorated housing projects, extraordinarily high crime and murder rates, and one of the worst public education systems in the country.

Major newspaper editors and TV producers have prepared very few reports about issues of race in this disaster, and those reports that have appeared so far seem to me deeply insufficient in their analysis of endemic class and race problems. I've been communicating with a national magazine reporter friend of mine since Tuesday night about the issues of race and class in this catastrophe; here's my email comment on this topic from earlier today:

CNN addressed the race question today on TV, but only to ask softball questions of Jesse Jackson, who to his discredit didn't exhibit even a modicum of the anger of one Louisiana black political leader, who said: "While the Administration has spoken of 'shock and awe' in the war on terror, the response to this disaster has been 'shockingly awful.'"

The Washington Post also ran a puff piece that doesn't ask any of the relevant questions, such as whether the Administration's response would have been faster if these were white people suffering the agonies of a slow motion disaster. Here's the link to the Post's piece.

Michael Moore also had this to say in a letter to President Bush circulated today:

No, Mr. Bush, you just stay the course. It's not your fault that 30 percent of New Orleans lives in poverty or that tens of thousands had no transportation to get out of town. C'mon, they're black! I mean, it's not like this happened to Kennebunkport. Can you imagine leaving white people on their roofs for five days? Don't make me laugh! Race has nothing — NOTHING — to do with this!

(See Michael Moore's full letter here.)

A member of the Congressional Black Caucus had to remind reporters today to stop referring to those displaced by the flooding with the blanket term "refugees" (recalling, of course, the waves of Haitian or Central American or Southeast Asian refugees who sought shelter in the US): these people are citizens, she said, deserving of the full protections guaranteed to all Americans.

The federal government promised on Wednesday that those receiving food stamps could get their full allotment at the beginning of September, rather than the usual piecemeal distribution throughout the month. How very generous. What these people need is relief money and access to services now — even the 50,000 or so exhausted and traumatized people whose images we've seen at the N.O. Superdome and at the Civic Center are just a few of the far larger number of those residents of the region displaced by the hurricane, many of whom live from monthly paycheck to paycheck. It will be months at the very least before these people can return home; their jobs may be gone for good. The mayor of New Orleans was actually caught off camera crying in frustration today at the slow pace of the federal response.

If there is a hopeful side to this tragedy, it is perhaps that Hurricane Katrina's damage and efforts to relieve those displaced by the storm may spark a wider national discussion about the ongoing and unaddressed issues of race and economic disparity in America. If that doesn't happen, I fear that there will be even further deterioration in the living conditions and economic predicament of those left destitute and homeless by Katrina — a situation in which our own government's years of neglect must be included as a crucial contributing factor. We must not let such a deterioration of conditions for those hardest hit by Katrina occur.

What happens next, when tens or hundreds of thousands of Americans require long-term recovery help, will be an important barometer of our society's ability to heal itself.

—Lincoln

4 Comments:

How many copters do you think you can fly around the city at the same time? You are focusing your anger on the wrong people. The people of N.O. helped elect the governor and they got what they elected. SHE had control over the evacuation and the initial rescue efforts. The state has access to hundreds if not thousands of busses, but Blanco could not decide what to do or where to send the people. FEMA initially had no reason to send food to people the governor said she was going to evacuate! They sent the food to the shelters. And then the "hoodlums" started shooting their own city up hampering the rescue efforts greatly. White people don't do that. That's not FEMA's fault, either. When you encourage a dependent society for your own political purposes, it comes back to bite you in a crisis. It is absolutely ridiculous to suggest that this is the fault of the federal government or that it has anything to do with race!

I don't believe this has a THING to do with race. I am employed by one of the radio stations in town that has been doing 24 hour coverage and information, so I have been glued to the fax machine and the TV for the past four days. I DO believe that the response to the disaster was not quick enough and perhaps could have been much more efficient had we not had our entire military resource exhausted in Iraq. However, I think we have to keep in mind that it was very difficult, and to an extent still is, to access the New Orleans area. The relief effort in Biloxi was much stronger, partially because the city was easier to reach and partially because the preparations, I believe, were slightly better in that area. I also agree with the prior comment that the shootings and debauchery of the evacuees greatly hindered the process. The Red Cross, at one point, said they would not provide anymore help until security was increased after one of their volunteers was shot in the leg. That kind of behavior is absolutely ridiculous. I feel bad for the people in New Orleans. I genuinely do. I am doing as much to aid the relief effort as I am financially and physically able to do, as well as informing the public on a daily basis via the radio station. But by the same token, I believe the effort in New Orleans is moving as well as possible and CERTAINLY has nothing to do with the race or class status of the people who have been trapped. I'm so tired of the Bush-bashing bullshit (scuze the language). I've heard Kanye West (a rapper) say "Bush doesn't care about black people". People are just trying to find ways to bash the President and using this as an excuse to do so. While I don't agree with many of his policies, this is not entirely his fault, and certainly has no racial implications.

washingtonpost.com

'To Me, It Just Seems Like Black People Are Marked'

By Wil Haygood

Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, September 2, 2005; A01

BATON ROUGE, La., Sept. 1 -- It seemed a desperate echo of a bygone era, a mass of desperate-looking black folk on the run in the Deep South. Some without shoes.

It was high noon Thursday at a rest stop on the edge of Baton Rouge when several buses pulled in, fresh from the calamity of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.

Hundreds piled out, dragging themselves as if floating through some kind of thick liquid. They were exhausted, some crying.

"It was like going to hell and back," said Bernadette Washington, 38, a black homemaker from Orleans Parish who had slept under a bridge the night before with her five children and her husband. She sighed the familiar refrain, stinging as an old-time blues note: "All I have is the clothes on my back. And I been sleeping in them for three days."

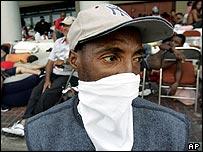

While hundreds of thousands of people have been dislocated by Hurricane Katrina, the images that have filled the television screens have been mainly of black Americans -- grieving, suffering, in some cases looting and desperately trying to leave New Orleans. Along with the intimate tales of family drama and survival being played out Thursday, there was no escaping that race had become a subtext to the unfolding drama of the hurricane's aftermath.

"To me," said Bernadette Washington, "it just seems like black people are marked. We have so many troubles and problems."

"After this," her husband, Brian Thomas, said, "I want to move my family to California."

He was holding his 2-year-old, Qadriyyah, in his left arm. On Thomas's right hand was a crude bandage. He had pushed the hand through a bedroom window on the night of the hurricane to get to one of his children.

"He had meat hanging off his hand," his wife said. They live -- lived -- on Bunker Hill Road in Orleans Parish, a mostly black section of New Orleans.

When the hurricane hit, Thomas, a truck driver, said he came home from work, looked at every one of the people he loves, and stood in the middle of the living room. Thinking. He's the Socrates in the family -- but time was running out.

"I only got a five-passenger car," he said.

"Chevy Cavalier," said his wife.

"And," Thomas continued, "I stood there, thinking. I said, 'Okay, it's 50-50 if the water will get through.' "

Within hours the water rose, and it kept rising.

"But then I said, 'If we do take the car, some of us would be sitting on one another's laps.' And the state troopers were talking about making arrests."

Instead, he pushed the kids out a window. They scooted to the roof, some pulling themselves up with an extension cord.

"The rain was pouring down so hard," Washington said. "And we had a 3-month-old and a 2-year-old."

The 3-month-old, Nadirah, was sleeping in her mother's arms. "All I had was water to give her," said Washington, her voice breaking, her other children sitting on the concrete putting talcum power inside their soaked sneakers. "She's premature," she went on, about the 3-month-old. "She came May 22. Was supposed to be here July 11. I had her early because I have high blood pressure. Had to have her by C-section."

Bernadette Washington was suddenly worried about her blood pressure medicine. She reached inside her purse. "Look," she said. "All the pills are stuck together."

Both parents had been thinking about the hurricane, the aftermath, the looting, the politicians who might come to Louisiana and who might not. And their own holding-on lives, now jangly like bedsprings suddenly snapped.

"It says there'll come a time you can't hide. I'm talking about people. From each other," Bernadette Washington said.

Thomas, the philosopher, waved his bandaged hand. He had a theory: "God's angry with New Orleans. It's an evil city. The worst school system anywhere. Rampant crime. Corrupt politicians. Here, baby, have a potato chip for daddy."

The 2-year-old, Qadriyyah, took a chip from her daddy and gobbled it up. Her face was covered with mosquito bites. But she smiled just to be in daddy's arms.

Thomas continued: "A predominantly black city -- and they're killing each other. God had to get their attention with a calamity. New Orleans ain't seen an earthquake yet. You can get away from a hurricane but not an earthquake. Next time, nobody may get out."

In the middle of the storm, little Ernest Washington, 9, had grown into a hero.

Washington and Thomas consider Ernest, Bernadette's nephew, their own now. They adopted him after his mother, Donna Marie Washington, died not long ago of AIDS.

"She was a runaway," said Washington, able to sound sorrowful for the child even in her current straits. "She had run away when she was 14. We don't know how she got the AIDS."

While Thomas was figuring his family's fate that first night, little Ernest bolted to the rooftop.

He had fashioned a white flag on a piece of stick, and began waving. "That is one courageous boy," Thomas said.

A helicopter passed them by. A National Guard unit passed them by.

"Black National Guard unit, too," piped in Warren Carter, Washington's brother-in-law.

In the South, the issue of race -- black, white -- always seems as ready to come rolling off the tongue as a summer whistle. A black Guard unit, passing them by. Something Carter won't soon forget.

Before long the whole family, watching the water rise, made it to the roof. Three men in a boat -- "two black guys and an Arab," Washington said -- rode by and left some food on the roof of a van parked nearby. Ernest went and retrieved the food.

"A little hustler he is," Thomas said.

"Child [is] something else," Washington said.

It took two days for a helicopter to fetch them. They were delivered not to some kind of shelter, but to a patch of land beneath a freeway.

"I thought we were going to die out there," Bernadette Washington said. "We had to sleep on the ground. Use the bathroom in front of each other. Laying on that ground, I just couldn't take it. I felt like Job."

Then, somehow, a bus, and then Baton Rouge. At that moment, a lady -- white -- came by the rest stop and handed her some baby items.

"Bless you," Washington said.

That exchange forced something from Warren Carter: "White man came up to me little while ago and offered me some money. I said thank you, but no thanks. I got money to hold us over. But it does go to show you that racism ain't everywhere."

Under the hot sun, Brian Thomas was staring into an expanse of open air. They expected another relative to arrive soon and assist them in continuing their exodus.

© 2005 The Washington Post Company

I really enjoy your blog.

Post a Comment

<< Home